Our purpose and strategy

Our purpose is Helping Britain Prosper.

The UK’s shift to electric vehicles (EVs) and transportation is accelerating.

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) made up 19% of new car registrations in 2024 while new registrations of petrol, diesel and hybrid cars dropped slightly. Yet combustion engines still dominate, making up more than 90% of all cars on the road. Their impact on climate, air quality and health remains significant.

BEVs are a critical technology that can deliver a clean, sustainable transport system. Lloyds is committed to supporting the transition to BEVs. We have provided over £10 billion in financing for EV and plug-in hybrid vehicles since 2021 and have undertaken significant work to challenge myths and provide evidence-based insights on BEV adoption.

This report, developed in partnership with Frontier Economics, outlines new evidence on consumer perceptions and the extent to which misperceptions may be holding back adoption across different groups of people.

This study draws on an online survey of 2,187 UK individuals who purchased a car within the last two years. Respondents answered questions about BEV features and tested their perceptions. Results were benchmarked against real-world data to quantify perception gaps; and segmented by demographics and behaviours to identify the groups most affected.

The findings highlight where misperceptions are strongest and where action is most needed. They provide a guide for the Government and industry to keep the transition on track. Addressing these misperceptions will ensure that the move to cleaner transport is fair, inclusive, and benefits everyone in the UK.

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) represents a pivotal moment in our journey towards a sustainable future. As we navigate this transformative period, it is crucial to ensure that the benefits of EV adoption are accessible to all segments of society. This report, illustrates a critical finding: lower-income individuals, who stand to gain the most from the use of EVs, are the least informed about them.

Our analysis shows that consumers have a good understanding of some of the main expenses of owning a battery electric vehicle (BEV), but they hold significant misperceptions around key features of what it is like to own a BEV, which are likely acting as barriers to the uptake of BEVs in the UK.

The perceptions of lower income households towards BEV use are significantly more negative than those on higher incomes. But having experience driving a EV, or even knowing others who do, has a huge impact on resolving most misperceptions.

1. The UK has set ambitious targets for the green transition in transport, with a progressive zero-emission vehicle mandate that will culminate in a ban on the sales of new petrol, diesel and hybrid cars by 2035.

To deliver this, the Government has introduced several measures to promote EVs, ranging from investment in charging networks to incentives that support consumer adoption.

2. More recently, the policy focus has widened to view the transition not just as an environmental and public health necessity, but also as a driver of economic growth.

The Leeds reforms announced at this year’s Mansion House identify the financial services industry as central to driving UK competitiveness, with sustainable finance and the green transition identified as priority areas for investment.

3. This positions the UK’s transport decarbonisation agenda not only as a route to Net Zero, but also as a means to boosting the economy, improving wellbeing, and establishing the UK as a global leader.

Achieving this will require coordinated action from the Government, the transport industry and financial services firms.

As a leading financial institution, we are committed to playing our part in driving investment, empowering consumers to make informed choices, and ensuring the benefits of the transition are shared across society. This report is part of that contribution.

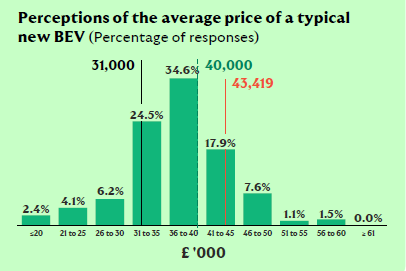

Consumers have a good sense of the upfront expense of a BEV. When asked to estimate the price of a typical new BEV, most people guessed it would cost around £40,000 – which is close to the true value of £43,419.

The charts in this report show the distribution of survey responses as well we the median response and true answer.

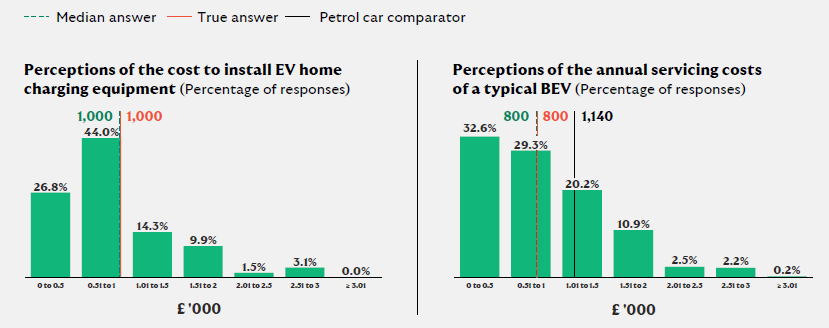

People also have a good understanding of some of the other costs associated with having a EV.

Perceptions of how much it costs to install EV charging equipment at home are very close to reality – the median answer in our survey was £1,000, which is in line with the average cost for this equipment.

Consumer perceptions of the annual servicing costs of BEVs are also close to reality.

And don't realise how inexpensive home charging is.

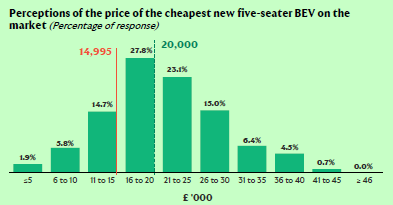

The average consumer thinks that the cheapest new five-seater BEV on the market costs £20,000, when in reality it is 25% cheaper: the Dacia Spring costs just £14,995.

Less than 15% of consumers thought that the price of the cheapest BEV currently available is between £10,000 and £15,000 and most guessed that it would be significantly more.

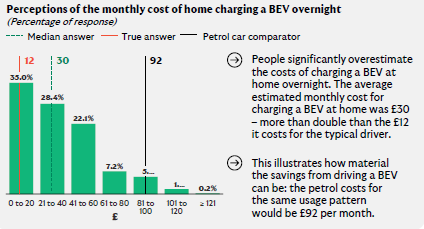

The higher upfront cost of EVs compared to petrol vehicles can be offset by the lower ongoing costs of charging at home overnight.

78%

of electric vehicle drivers surveyed used a public charging point less than twice last month.

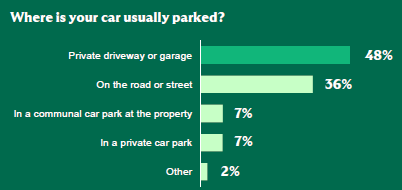

Considerations around home charging are very important to consumers. Not being able to charge an EV at home was the third most important stated barrier to BEV take-up.

22%

of consumers said that not being able to charge at home was among their top three reasons for not purchasing a EV.

But out of consumers that chose this option, nearly half keep their car on a private driveway or in a garage, which means that they would most likely be able to install BEV charging equipment at home.

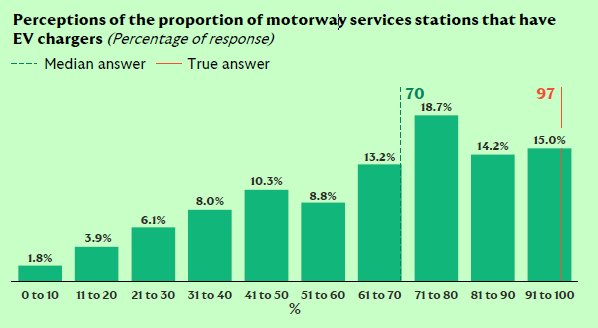

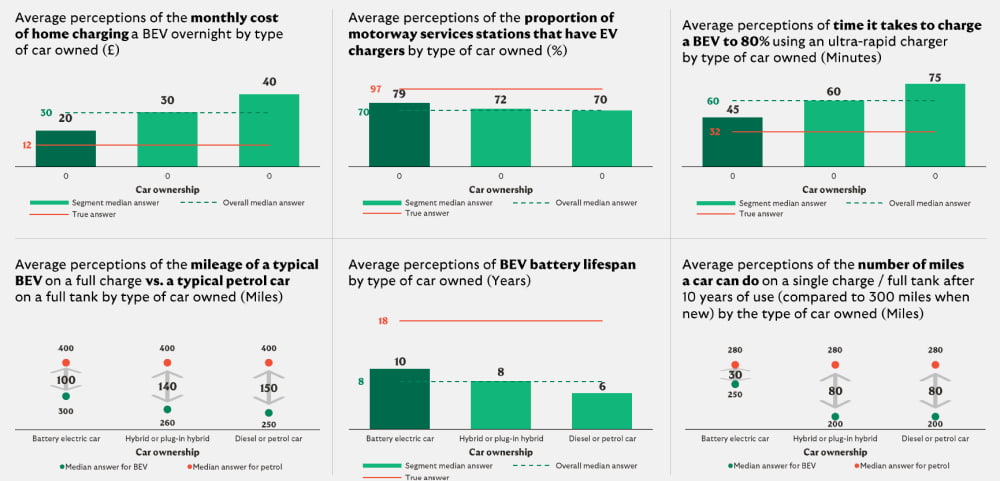

People on average estimate that only 70% of UK motorway services stations have EV chargers. The true figure is 97%.

Only 15% of consumers guessed that over 90% of UK motorway services stations have EV chargers.

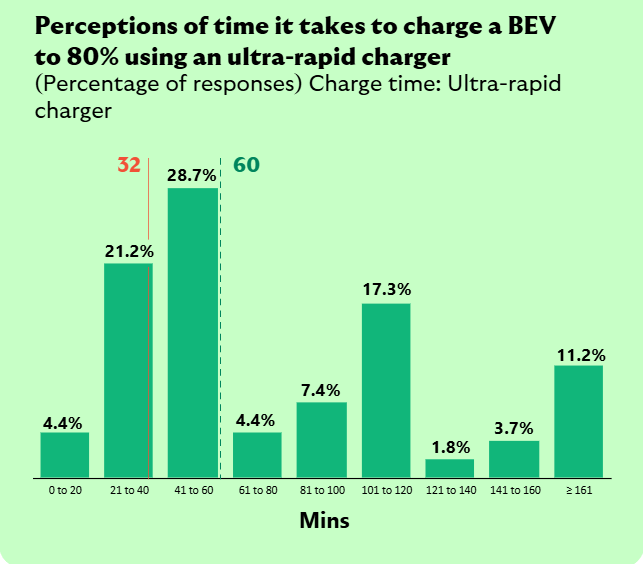

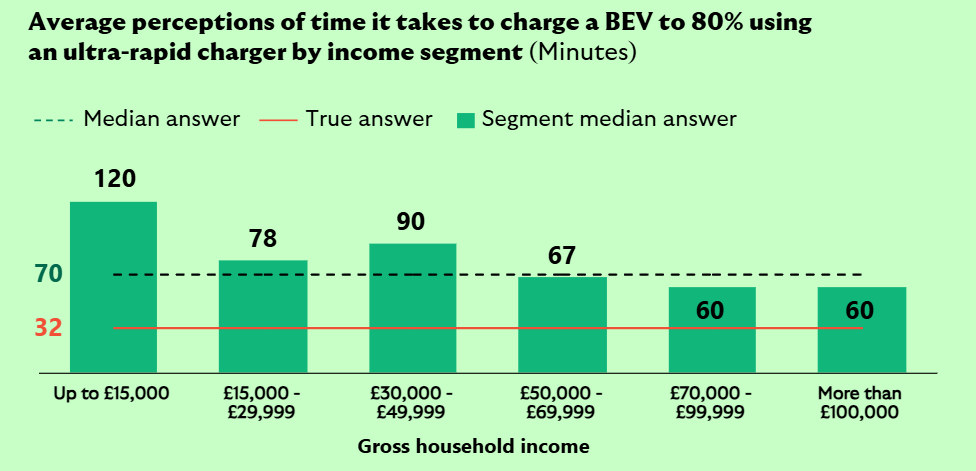

Consumers believe that it takes much longer to charge a BEV using an ultra-rapid charger than it does: the average estimate to charge a BEV to 80% was 1 hour, when in reality it takes only about half that time.

People underestimate the range of BEVs: a typical BEV can go 311 miles on a full charge, but the average estimate in our survey was 250 miles. Over a third of people thought that the typical BEV had a range of less than 200 miles.

Misperceptions over range are not limited to electric cars. The average estimated range for a comparable petrol car was 400 miles, when in reality it is closer to 460 miles. But the much lower estimates for BEVs may create more ‘range anxiety’ for consumers.

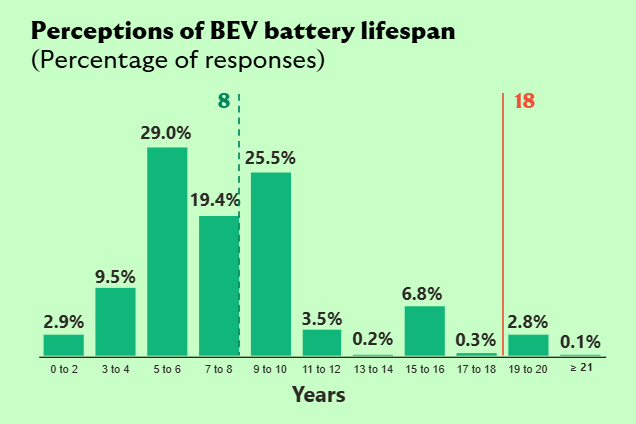

People think that the battery of a typical BEV lasts only 8 years before it needs to be replaced. This is likely to be impacted by the 8-year battery warranty period.

In reality, some sources suggest modern batteries may outlast the vehicle itself – with an average lifespan of 18 years. Less than 5% of consumers guessed that batteries could last 18 years or more.

44%

of consumers believe that a petrol car can do the same number of miles on a full tank after 10 years of use as a new one.

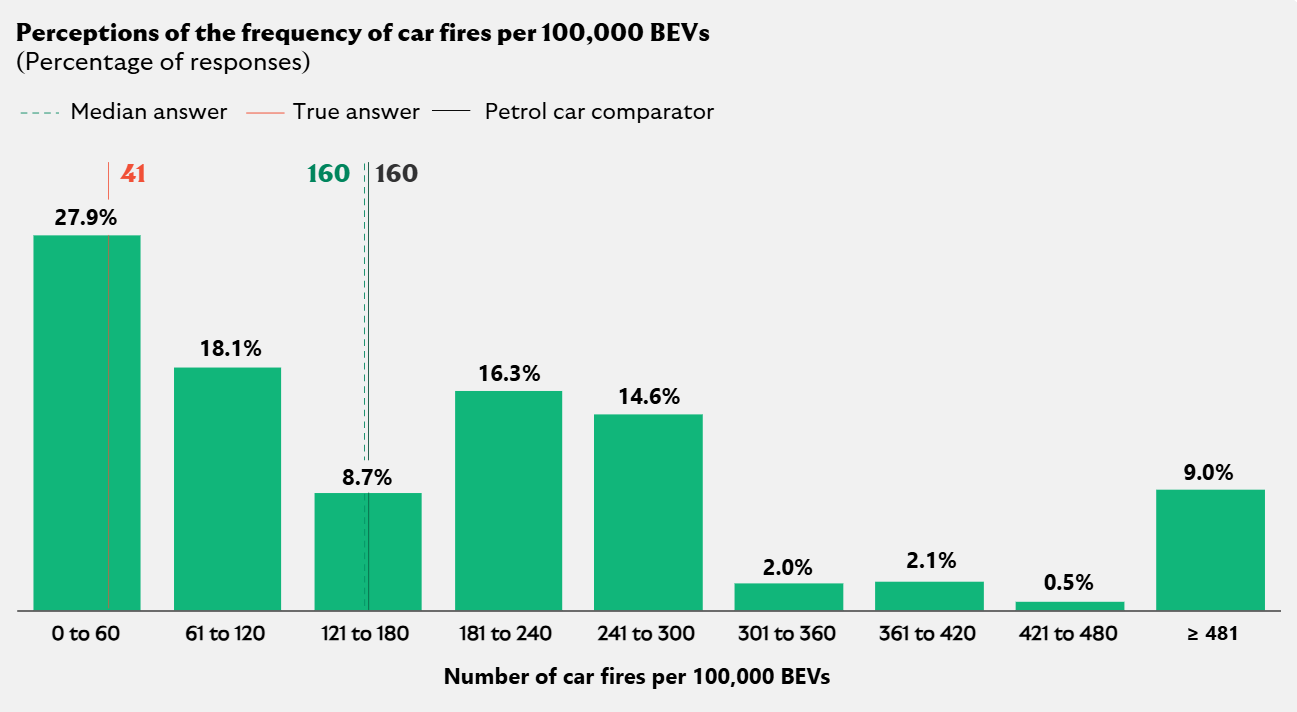

Electric car fires have received significant media attention in recent years and have potentially contributed to the barriers of BEV update.

Consumers significantly overestimate the fire risk of BEV: the actual rate is just 41 incidents per 100,000 cars, but the average estimate in the survey was 160 incidents per 100,000 cars – the same as for petrol cars. In reality, the risk of a BEV catching fire is much lower than that of a petrol car.

Compared to higher income households.

In addition to underestimating the savings from home charging a BEV, lower-income households are more pessimistic towards other elements of BEV use.

While consumers generally overestimate the time it takes to charge a BEV to 80% using an ultra-rapid charger, the lowest income groups believe that this takes significantly more than an hour, while those on the highest incomes believe the figure to be closer to an hour.

Those on lower-incomes also tend to underestimate the range of a typical BEV more than other consumer groups.

Among those with a household income under £15,000, the average person expects the difference in the range between a petrol car and a BEV to be 200 miles while other groups believe it to be around 150 miles.

In practice, the actual difference is about 150 miles (with an average of 458 miles for petrol cars versus 311 miles for BEVs).

Our analysis shows that people that have experience driving a BEV hold significantly more positive attitudes towards BEVs and have fewer misperceptions around their use. This is also true to a lesser extent for hybrid drivers.

This result holds across perceptions of the cost of charging, the coverage of charging equipment and the speed of charging, range, battery performance and degradation.

This is to be expected given these drivers will have real world (and positively reinforcing) experience of using a BEV.

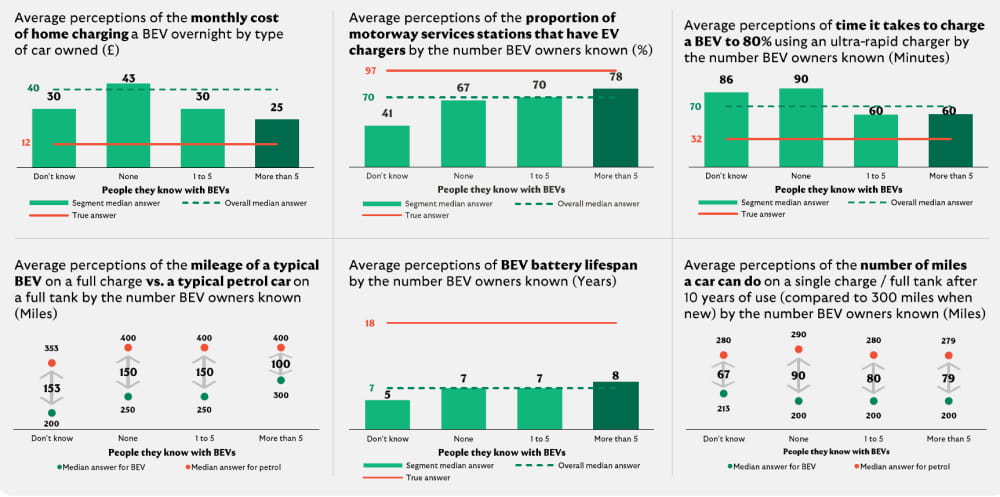

Even the consumers who do not own a BEV themselves are more positive and accurate in their perceptions towards BEVs if they have friends or family members who own a BEV.

This is broadly true across perceptions of the cost of charging, the coverage of charging equipment and the speed of charging, range, battery performance and degradation.

This suggests that BEVs becoming more commonplace is likely to generate positive network effects where consumer perception barriers can be overcome simply by being more exposed to BEVs through other people in their lives.

The perceptions of lower income households towards BEV use are significantly more negative than those on higher incomes.

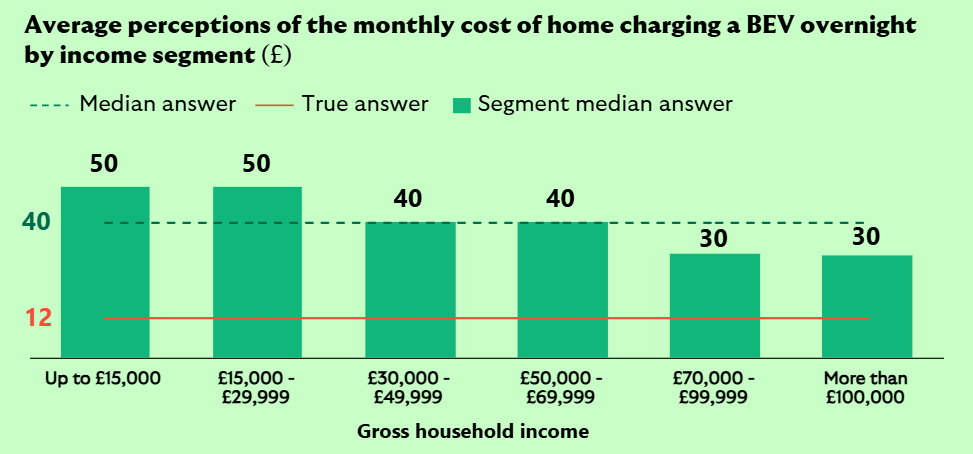

This is evident in the difference in the perceptions towards the cost to charge a BEV at home overnight between different income segments.

Although all consumer segments overestimate how expensive home charging is, lower income households expect BEV charging costs to be much more (£50/month) than those on the highest incomes (£30/month).

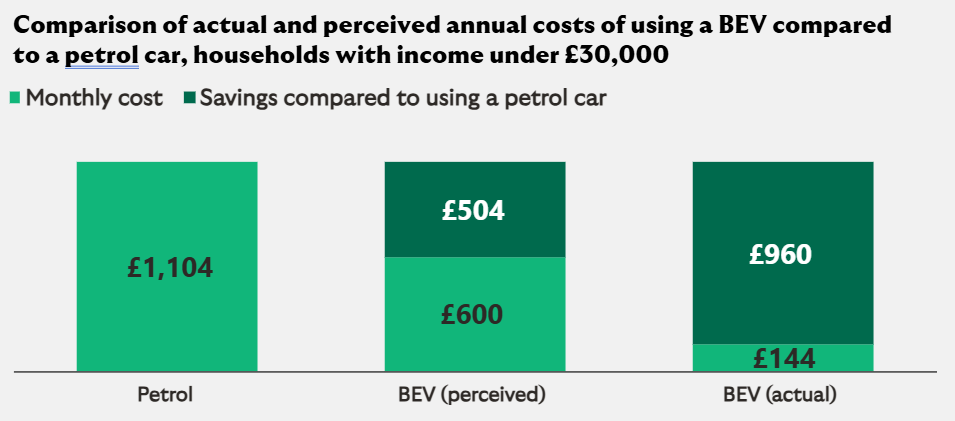

A typical driver spends £92/month or £1,104/year on petrol. This equals about 4% of the annual net earnings for a family with a household income of £30,000.

The average savings that lower income groups would expect to make from switching from petrol to a BEV would be £504/year, assuming all charging takes place at home overnight.

The real savings that lower income groups could realise on average are £960/year, or nearly 2.5% of the net income for someone earning £30,000.

The Government has made a clear commitment to transitioning the UK away from petrol and diesel cars towards BEVs and this is supported by a wide range of existing policies to achieve Net Zero.

This report has highlighted key areas where consumer uptake of BEVs is limited not purely by factual considerations but may instead be driven by misperceptions. The misperceptions fall into five areas:

1. We find that those earning less than average and have the most to gain from switching from petrol to much cheaper BEV home charging hold the strongest misperceptions and negative attitudes towards BEVs. Exposure to BEVs, on the other hand, whether direct or through friends and family, goes a long way to dispel these myths.

2. Given these network effects, it is important for the Government and industry to ensure that as BEV adoption grows, some consumer groups – particularly those that do not spend time with people that already own BEVs – do not get left behind.

3. Given these findings we propose a set of policy recommendations for the Government to take forward to support the work already being done as it seeks to accelerate the electric transition on the nation’s roads. We also outline the actions that the industry could take to address the barriers and misperceptions highlighted in this report.

It takes about 32 minutes to charge a typical EV from 0% to 80% using an ultra-rapid charger at a motorway service station. Read more about charging an EV.

A typical battery electric vehicle (BEV) can travel 311 miles on a full charge.

Charging a BEV at home overnight costs about £12 per month for a typical driver (600 miles), compared to £92 per month for petrol for the same distance. Read more about the cost of electric vehicles.

Yes, EVs can save a typical driver around £960 per year compared to petrol cars, especially when most charging is done at home.

You can use public charging stations, which are widely available. 97% of UK motorway service stations have EV chargers, and there are increasing numbers of chargers in public and communal car parks.